And there were smells, powerful smells, interesting smells -- garlic, incense, cooking, fireworks, kerosene, wood fires, exhaust fumes, open sewers, animal odors. Some good smells and some really bad smells!

All of the war material, supplies, ordnance, and personnel used in China was flown in over the "hump." Most of it came into Kunming, which made Kunming, at that time and maybe anytime ever, the busiest airport in the world. Planes were landing and taking off 24 hours a day without pause. At times, incoming flights were stacked at 500-foot intervals up to 25,000 feet in several different zones around the field.

Our flight was on

alert every night, from dusk to daylight. Our fighters scrambled

many times when incoming planes didn't identify themselves, or when

their IFF equipment failed to operate, turning them into bogies.

IFF -- Identification Friend or Foe -- was a radio transponder that was

in all allied aircraft. It would answer a query signal with a

coded response. The code was changed regularly, but the system

didn't always work. In these cases, landings would be suspended

while we "scrambled" and GCI vectored us to within range of the

"bogie." GCI -- Ground Control Intercept -- was a controller

located on the ground Through the use of more powerful radar and

other intelligence, GCI would direct fighter aircraft to within range

of a target. We would then make a final interception on radar and

identify the target -- in every case, a C54 cargo carrier or a C46 or

some other "friendly" type. Following this, GI would call off the

alert and normal traffic would recommence.

Our flight was on

alert every night, from dusk to daylight. Our fighters scrambled

many times when incoming planes didn't identify themselves, or when

their IFF equipment failed to operate, turning them into bogies.

IFF -- Identification Friend or Foe -- was a radio transponder that was

in all allied aircraft. It would answer a query signal with a

coded response. The code was changed regularly, but the system

didn't always work. In these cases, landings would be suspended

while we "scrambled" and GCI vectored us to within range of the

"bogie." GCI -- Ground Control Intercept -- was a controller

located on the ground Through the use of more powerful radar and

other intelligence, GCI would direct fighter aircraft to within range

of a target. We would then make a final interception on radar and

identify the target -- in every case, a C54 cargo carrier or a C46 or

some other "friendly" type. Following this, GI would call off the

alert and normal traffic would recommence.Intercepting friendly planes was disappointing and frustrating. We took some serious kidding from day fighter people about "midnight joy rides" and so on. The 426th had already gotten a bad name because there had been a number of unjustified mission aborts which led to confusion during alerts and used gasoline that was already in short supply. Our morale was low because of it and, in addition, it seemed to us that "D" flight was given the dirty end of the stick. The aircrews assigned to us were the squadron misfits. The planes we were given were the least qualified. And to top it all off, we were resented by other squadron members because we newcomers outranked most of them and consequently were made "D" flight leaders over other fellows looking for promotion.

It happened that about this time we got a letter from a training school friend "Sollie" Solomon, with a squadron on Formosa. Sollie was in a good outfit, flying productive missions, and he wished we would find some way to transfer and join him. We inquired, but transfer was impossible. Sollie was in the South Pacific and we were in China. Only 1200 miles separated our two bases and we got the idea that we could easily fly that far and no one would be particularly sorry to see us go. We could claim that we got lost chasing bogies and with low fuel had to make for Formosa. We might get a reprimand, but they would never court-martial us, and they would certainly never send us back. We couldn't get this idea out of our minds. But there were problems. Navigation would be tricky, and we had no charts of the Formosa area. In fact, all of our charts were unreliable, having been prepared from 19th century explorer's notes that were incorporated into National Geographic's sketchy data, which the Air Corps made into charts. Another problem was the weather, which could be unpredictable in the South China Sea, and could do us in.

We started a search for charts by talking with crewmen from ATC (Air Transport Command -- primarily a personnel mover, like an airline but with no amenities, not even seats sometimes), and we guardedly asked our weather officer, Dave Griffith, about how South China and Formosa weather information might be obtained. The plan we developed was to check our destination's weather every day so that the next time we were scrambled, and the weather was favorable, we would complete our local mission with GCI, then break radio contact and fly to Formosa and a new squadron.

We found the needed charts, but our questions about the weather 1200 miles away made Dave suspicious. He confronted Ab and me with his conclusion that we were leaving the squadron. That being the case, in a spirit of adventure, he wanted to go with us. As flight leader we had authority to take non-flying personnel on flights or even missions if there was justification. So we decided Dave could fly on the pretext that he wanted to make a night inspection of the Kunming area terrain, and to make some related solar observations He promised absolute secrecy and started standing alerts with us. A few days later, Formosa weather was clear and we were scrambled to chase a bogie that we intercepted and confirmed as friendly. GCI called off the alert and ordered "Oscar" (our identification code name) back to base. We responded, "Roger," but swung onto a heading for Formosa, 1200 miles away, through a hazy, moonless night. GCI started calling after about 30 minutes, wanting a position report and getting no response. They called again and again until their VHF transmission started breaking up and finally disappeared because of increasing distance. We expected our flight to take six hours and we had enough fuel in belly tanks to provide a margin of safety, but two hours into the flight our radar malfunctioned.

The radar was essential to our navigation across the South China Sea to Formosa. Without radar, we could drift just a few degrees off course and miss the island in darkness. Working only with the radar's manual controls, I was able to get an accurate reading on our terrain altitude and we pressed on, thinking "Formosa's a big island, and with terrain altitude we can at least tell when we make landfall." We would then be able to raise somebody on the island on one of our radio channels.

Then, three hours into the flight, the radar picture made a further change. In the unreliable terrain image I was looking at, there were suddenly large polka-dot blips. When we circled, the blips showed up on the terrain all around us. I had never heard of such a signal return before and nothing like it was described in our training manuals. There was no logical explanation for this kind of presentation on our scopes and further reliance on our radar was impossible. We were 600 miles into the flight. If we continued, we would soon pass the "point of no return." We decided we had to go back to Kunming.

Two hours later, we raised GCI, who thought we had gone down. They were so glad to hear from "Oscar" that they believed our story about "when our radio and radar went out, we got lost thinking we were south of the field, when actually we were east. And then the radio somehow started functioning again." It was dawn when we landed. We had been airborne six hours and we never told anyone where we had actually been.

Forty years later, I came across an article in National Geographic magazine about Guilin, China, halfway between Kunming and Formosa. There were pictures of this area with strange sheer hillocks a thousand feet high, strewn throughout the valley. I knew instantly they were the polka dot blips I had seen on my radar screen that aborted our mission that night.

Later on, there was a night when the Japanese sneaked in a single bomber that made several low-level passes at the field, dropping clusters of small anti-personnel bombs. One of our planes was scrambled, but made no contact with the enemy. GCI never picked him up out of the myriad of our own planes in the air. I was on the field during this raid and under fire for the first time. With many noisy explosions close to me I was naturally afraid, but curious enough to take stock of what was happening. The field, not responding to any alert, was all lit up. The Japanese bomber had glided silently in to scatter his bombs all around us before slipping away under low power. I found a foxhole and settled in to watch for the next pass when a corporal we called "Big Stoop" (because of his size!) piled in on top of me. He apologized for the inconvenience, but at the time I appreciated the protection his 250-pound bulk provided, and thanked him.

On another occasion, we were on alert and were scrambled, chasing some friendly bogie, when there was an actual raid like the first one. A single plane, sneak attack. Suddenly, it was the real thing. GCI didn't pick up the enemy this time either, and there were dozens of our own planes in the air. My radarscope was lit up with targets and we had latched onto one bogie when Ab saw a stick of bombs exploding on the field and dove our plane toward this activity Almost immediately, we picked up a target that was approaching us head-on. We didn't realize in the excitement of this first combat confrontation that a situation had been created with our diving plane going perhaps 275 mph. When the two planes were within a few hundred feet, we made a 180-degree turn to swing in behind the target only to discover that with our 150 mph speed advantage, we were going much too fast. Within seconds we helplessly overshot the target. We maneuvered in a search mode trying to pick him up, but made no further contact and never saw the other plane that I am certain was a "bandit." I never stopped feeling badly about not having made that interception. I was supposed to be the "hottest RO" in the squadron, but I didn't feel like it and I got some looks from my squadron mates.

On Christmas Eve 1944 we had been scrambled and had intercepted several friendly bogies under GCI direction. There had been some radio dialogue between "Oscar" and GCI, code named "Tiger." It was cold and the mission had dragged on until midnight, when a different voice on our radio said, "Hello, Oscar, this is 'Donald Duck.' Merry Christmas!" The call sign "Donald Duck" belonged to General Clare Chennault. We wished the general a merry Christmas in return. Fighter control and GCI radio channels were monitored by the general 24 hours a day. Even when he slept, they said.

A few days later, we were replaced by a new night fighter squadron and ordered to Chengtu to join our squadron who, with the exception of the men in our flight, we had never seen.

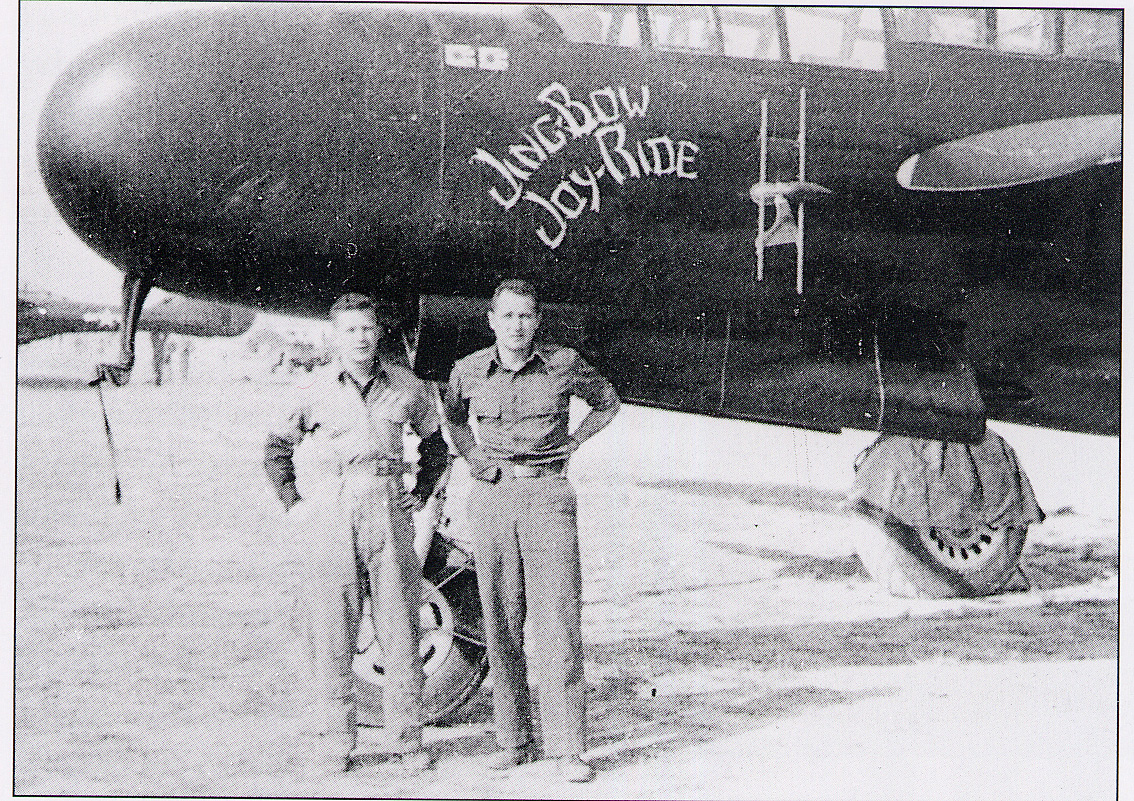

Photo: Smith and Absmeier pose by the nose of the Jing-Bow Joy-Ride, the P-61 that was with them throughout most of the tour.